Insurance Design and the Passthrough of Nominal Drug Prices

The cost of prescription drugs to U.S. health insurance plan sponsors depends on a nominal, publicly known “list” price, and a hidden rebate that’s individually negotiated with each payer. Over the last two decades, list prices have risen steadily, causing growing concern among policymakers. Yet, when faced with questions about these price increases, pharmaceutical industry stakeholders usually point out that prices net of rebates grow at much slower rates. This response, however, does not explain whether list prices matter, and why their growth has outpaced the growth of net-of-rebate prices in recent years.

Many argue that list prices matter for patients because virtually all health plans choose to peg coinsurance (the percentage patients pay at the pharmacy) to list rather than net prices. But it is not clear, from an economic perspective, why that makes sense, since list prices do not reflect actual acquisition costs. Moreover, evidence that higher list prices pass through to patient out-of-pocket (OOP) costs is actually very weak (Yang et al., 2020; Rome et al., 2021; Lalani et al., 2024).

In this paper, we argue that health plans have an incentive to peg coinsurance rates to list prices to bypass minimum coverage requirements. We then show that passthrough of list price increases to OOP costs happens primarily among these types of health plans.

A Theoretical Model of Health Plan Design with List Prices and Rebates

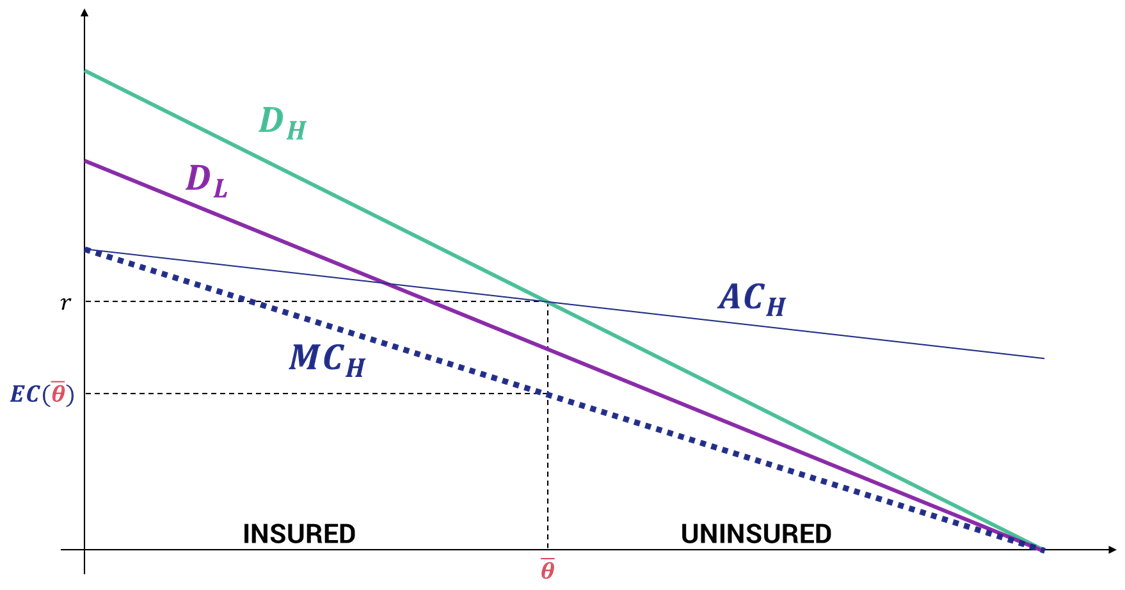

We develop a formal model of health plan design with adverse selection. Plans must satisfy a minimum coverage requirement defined as a maximum coinsurance rate applied to the drug’s list price. In this environment, increasing the list price while negotiating an equal-and-opposite rebate, allows a plan to raise the dollar value of a patient’s coinsurance payment while nominally remaining within the parameters of the coverage requirements. We show that offering these less generous plans at lower premiums is a profitable deviation from the initial equilibrium under very general conditions.

The key implication of the model is that only plans that are constrained in their benefit design will rely on list prices to increase patient OOP costs. In practice, plans in several US insurance market segments are subject to minimum coverage requirements. Medicare Part D plans must provide a minimum standard benefit design consisting of a pre-established set of coinsurance rates. Additionally, since the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2011, most commercial plans must spend a specific share of premium dollars on medical care. Another potentially relevant restriction arises from the nature of coinsurance rates, which are (in practice) capped at 100%. The rise in popularity of high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) suggests that at least some of these plans may want to increase cost-sharing for first-dollar healthcare spending above this cap.

Empirical Evidence of List Price Passthrough to Patient OOP Costs

To study this question we use retail prescription drug claims from commercial and Medicare Part D plans between 2007 and 2018 matched to data on drug list prices. Our main empirical specification compares within-drug changes in list prices to changes in patient OOP costs.

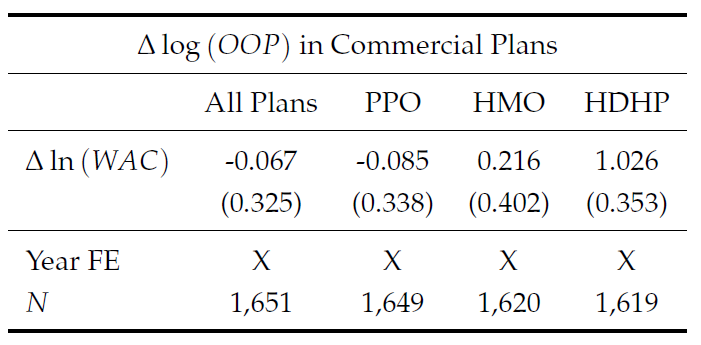

Table 1. Effect of list price growth on OOP cost growth in commercial plans

Because list prices and OOP costs are equilibrium outcomes that are likely affected by similar market forces, we use exposure to the Medicaid program as an instrument for list price growth, mitigating endogeneity concerns (we show in a previous paper that drugs with a high shares of sales to Medicaid patients increase list prices more slowly to avoid an inflation penalty that is part of the formula Medicaid uses to reimburse drug prices).

Table 2. Effect of list price growth on OOP cost growth in Medicare Part D plans

Our results show that list price increases translate into proportionally higher patient OOP costs in plans that face coverage constraints, but have no effect on the OOP costs of patients in “unconstrained” plans. “Constrained” plans include HDHPs (where sponsors may wish to increase coinsurance rates above 100%).

Implications

Our findings are significant for three reasons.

We show that higher list prices translate into higher OOP costs, confirming that the list-net price divergence is not a harmless accounting artifact but a source of real financial burden for patients. These findings support allegations in the Federal Trade Commission’s recent complaint against PBMs.

Our model implies that manufacturers benefit from higher list prices when negotiating with health plans. To see why, consider two identical competing drugs with the same net price, but different list prices. Sponsors offering plans that must offer a minimum level of coverage prefer covering the drug with the higher list price because it will have higher OOP costs, (which in turn allows the plan to lower premiums).

Our model also provides a reason why the list-net spread might benefit plan sponsors—rather than PBMs. If plan sponsors were the primary driver of the list-net price spread, it would explain why this spread has persisted even as PBMs have increasingly integrated with insurers and moved towards full sharing of rebates with payers.